treatise on time

treatise on time

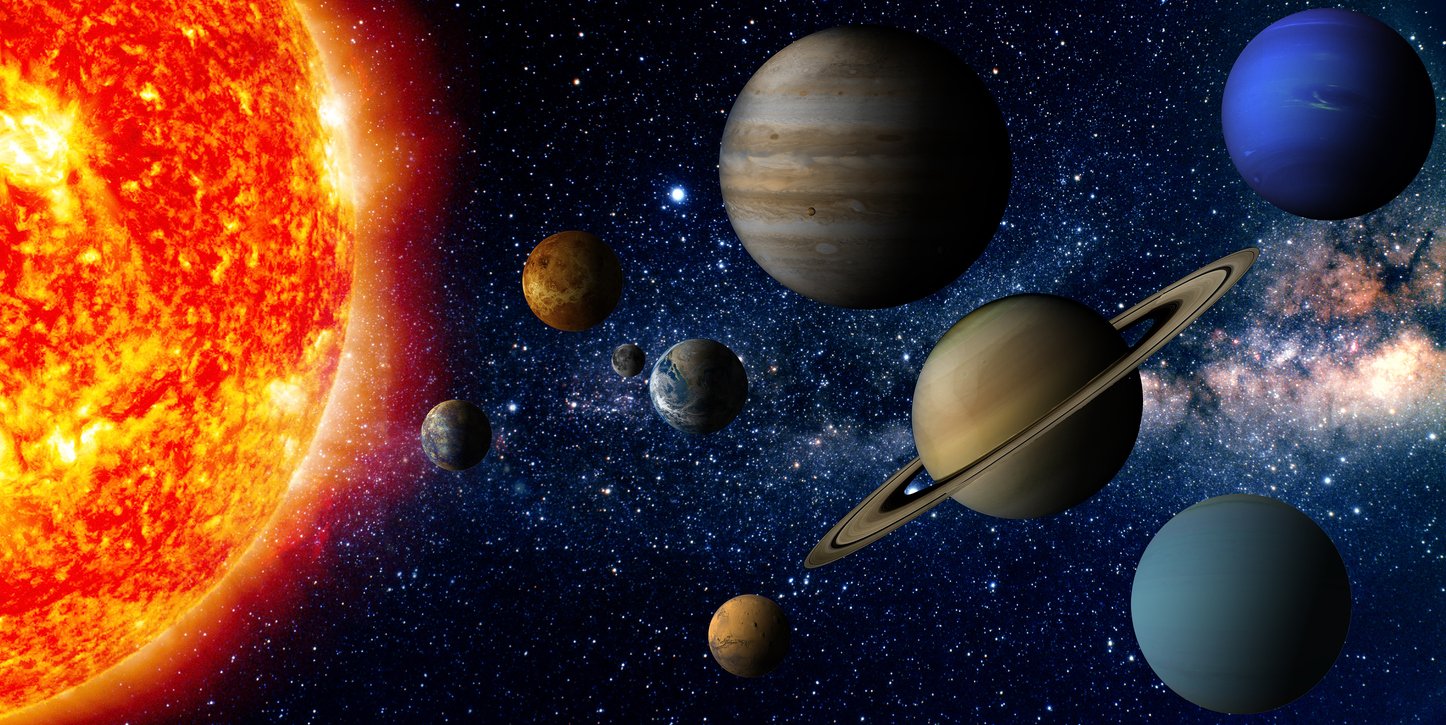

We exist in time. On a certain level, I know that time is a fantasy, an affectation, an illusion. We measure time by the revolution of our planet around its sun, the revolution of our planet around its own axis, and our singular moon revolving around our planet, giving us years, seasons, months—both solar and lunar—weeks, days, hours, minutes, seconds. Of course, none of this has any bearing beyond planet earth.

Think of existence as a book. There’s a beginning, an ending, and a bunch of things that happen sequentially between those first and last pages. When we read it, we read the sentences in order—it would make no sense if we read them randomly—and the story unfolds, one event following the one before it.

While we’re busy living life, day by day, we’re living sequentially in time, writing our personal chapters page by page, moment by moment, and organized into the past, the present, and the future.

We have to accept this concept of time, communally. We have to exist in time. Without the tick-tick-ticking of the clock, all would be random, chaos. We could accomplish nothing.

But just for a moment, let’s step out of time. Close the book, set it on the table, and walk ten paces away. Look. There it is. It’s all there at once. Everything from the moment of creation until the last moment of existence is happening at the same time, all the time.

It’s healthy to close the book and step away for a moment. It hones our perception, keeps us focused on the big picture and helps us keep perspective. It reminds us of the Greater Truth.

We could make a pact to do it three times a day, marking sunrise, noon, and sunset. And while we’re taking a “time out,” stepping out of time, let’s verbalize an affirmation. Let’s proclaim out loud, as a people, that all is one. That God, and God’s creation, are one. And, since we’re scattered across this planet, each speaking the language of our location, let’s decide to proclaim it in one language so that we can say it together. Let’s use the ancient language of our people to remind us of our roots and our unity. Ready? Let’s say it together: She’mah Yisrael, Adonai Eloheinu, Adonai Echad! Hear, Israel! Hear it with your ears, with your intellect and understanding, with your heart, with your organs and sinews, with your bones and your flesh, and with your soul—God—our God, is One.

And now, for the sake of functionality, for the sake of living a meaningful life within physical existence, let’s re-open the book at the same page where we left off and jump back in.

One of the ways that Jews mark time is with our festivals and holy days. At the full moon of the vernal equinox, we mark our beginning as a people with Passover, the festival of our liberation. We go forth and receive the Torah, mess up, lose our way for a bit, suffer the dire consequences, find our way back, and repent. Then, at the full moon of the autumnal equinox, we reap the goodness we have sown and celebrate the festival of the harvest, Sukkot. We live in flimsy little huts for the duration, to remind ourselves of the temporary nature of the physical, and we rejoice in it.

The days grow shorter, the darkness outweighs the light. Near the poles the light disappears altogether. And at the final phase of the moon in the final phase of the sun we celebrate Chanukah. For eight days, we light candles when the sun has left the sky, each night increasing the number of candles by one, to help usher in the return of the light.

And so, we exist in time, flowing organically in time—in rhythm with our planet—and out of time—with awareness of eternity. This is living life as a Jew.

Time is a gift. It’s a limited commodity. Yes, there are free refills, but you get a different cup.

I’d do well to respect it and use it wisely.