beresheet

parasha beresheet

First Parasha, genesis 1—10

menu

and thoughts…

Beresheet

or,

Here we go again, taking it from the top

So! Here we are again, back at the beginning of the Torah, and I’m wondering, what new revelations will this year’s reading of the same old words bring to my life?

Maybe I’m a Torah nerd, but I find Simchat Torah to be a really exciting time. I love the drama of hearing the very last verses of the books of Moses read, only to be immediately followed by the opening words of Genesis, Chapter One. It’s powerful.

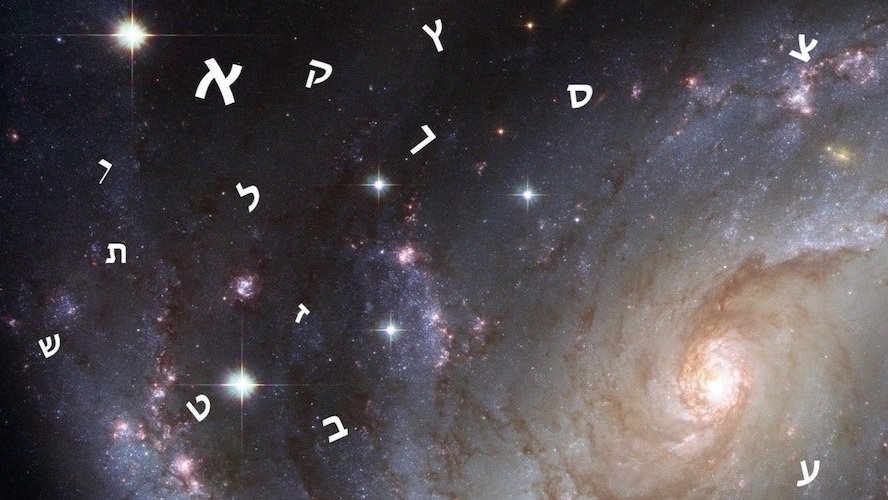

These first chapters are my favorite. (Is it ok to have a favorite?) Woven into the words are mystical concepts that, in my mind, are a key that unlocks all the secrets of the books of Moses, known to non-Jews as the Old Testament and to Jews as Torah.

The first chapters of Genesis are about creating, and they sure have created – created controversy that overflows the confines of religion into politics, public education, and our judicial system. Creationism or Evolution? Where is the truth? Does it reside in scientific discovery, or here in the opening passages of the Bible?

Can the answer be, all of the above? The next question almost asks itself: if scientists are right, if the universe is truly billions of years old, and if all life evolved from a single, carbon-based cell, is there any value to reading and studying the creation story of Genesis, yet again?

Let’s explore:

As beings of imaginative creativity, it is our nature …

Human nature is no different today from what it was 5,000 years ago. Even today, when we’re confronted by things beyond our understanding, it’s our nature to weave an explanation with the threads of known facts acting as the warp, and the threads of imagination as the weft. These complex tapestries can be quite rich and beautiful, and when we’ve grown up with them giving us comfort and decorating the walls of our minds, we’re not eager to unravel them, just to satisfy some newly emerged facts.

But what if we can accept those facts while keeping our tapestries intact?

Before we can decide if anything in the Torah is truth or fiction, I think we need to consider it, not from our sophisticated 21st century platform, but rather against the backdrop of the time and the culture from which it emerged.

If there’s one thing I’ve noticed about the universe in my years upon this planet, it’s that it makes sense, that it’s logical. It’s orderly, it can be expressed mathematically, it follows certain laws. I have no reason to believe that it has not always been so. Taken literally, the creation story seems ridiculous to the educated mind. Could the earth have been created and covered by lush vegetation, growing and reproducing in kind, before the creation of the sun, the moon, and the stars?

To our sages who lived at the dawn of the common era, the answer was, yes. It was common knowledge that the earth was a flat disc. Everyone knew that it was covered by a dome, called the firmament, and that the firmament held back the waters above it from drowning the earth. Clearly, if one looked from the horizon to over one’s head, one could see the curve of this dome. We could even see the waters above through the transparent skin of the firmament. Undoubtably, the sky is blue because the water above it is blue. Without the firmament separating the waters above it from the waters below it, life on earth could not exist. And so, all of this made perfect scientific sense: On day two, the firmament that separated the waters from the waters was created, and once the waters below were gathered together to separate the seas from the dry land on day three, any order of placement of stuff—on the earth, in the seas, and in the heavens—would be plausible, could work.

I don’t think anyone believes this anymore. Even the most heels-dug-in fundamentalist who lives today does not believe that the earth is flat and that the sun, moon, and stars revolve around it, or that if we pierce the sky, we will discover endless water above it. We’ve been to space and it is not liquid.

Every primitive culture has a creation myth. Genesis gives us two accounts, two myths to choose from. In chapter one we’re presented with a narrative. God says (to whom?), “let Us make Man in Our image.” And God does so – “male and female, God created them.” In chapter two, a different story is offered. God creates a human from the dust of the earth and breathes an animating soul into this new type of being. This human, Adam, notices that all the animals have counterparts, males and females, but Adam is alone. Adam is lonely. God puts Adam to sleep, removes one of Adam’s ribs, and from it creates a woman, Eve, for Adam. A third account can be found in the book of Isaiah. Isaiah offers a totally different scenario, one that is very much in line with the Canaanite creation myth.

Various biblical scholars have drawn parallels between the Torah’s story and the creation myths of Mesopotamia, the ancient Egyptians, and the Babylonians.

So, how can we say that Torah is history, that Torah is truth? After all, the Torah is not only at odds with modern discoveries, it’s at odds with itself. We can certainly say that Torah is truth in as much as it truly provides a window into the thinking and understanding of our people from our earliest inception. In that way, it’s part of our history.

But the Torah doesn’t claim to be a human account of Jewish history; the Torah claims to be the Word of God. If God is God, God would know the truth, would know the science of the origins of our universe. Would God tell us something that wasn’t true? Why doesn’t Genesis read like a scientific treatise, one that’s far beyond even our current knowledge base?

If we want to explain a complicated concept to a young child, we need to do it in much more simplistic terms than we would use to discuss it with a peer. There’s no sense in explaining the mathematics of relativity to a three-year-old. Perhaps God was telling a story to people who lived four thousand years ago, in terms they could understand, taking into account their exposure to the myths of other peoples of the Ancient Near East. And, perhaps God buried ultimate truth in the spaces between the words, to be discovered when we were ready to understand.

What’s interesting is how our creation myth differs from those of our ancient neighbors.

First of all, we don’t begin with a panoply of gods, fighting one another for supremacy. God is One. God is always One. God doesn’t couple with humans to give birth to demi-gods. Another critical difference is that God is not corporeal; at the end of the creation period, God does not settle himself into a temple, where he will abide. God exists in time, not in space. God is formless and omnipresent.

But to me, the extraordinary, amazing thing about the Torah is that it’s always relevant. Here’s why—For thousands of years, the story was accepted as literal, unquestionable fact. Over the centuries, advances in technology and communications have, generation by generation, unraveled the threads of imagination that were woven into that tapestry of what we know. But through those same words of Torah, those threads of imagination have been replaced with metaphorical and mystical truths that fill in those spaces even more profoundly than did the literal interpretation of ancient days.

Every generation interprets the words of Torah in its own way, within the framework of its time, and within any generation, each reader will derive something different, unique to their intelligence, personality, and current life experiences. And what’s even more remarkable is that each of us will discover new revelations with every reading, with every turning of the wheel of the year, in accordance with our own personal journeys.

God always, has always, and always will speak to humanity in terms that humanity can grasp, and understanding is an evolving process for us. A God Who finds the exact words that always have this extraordinary power for us, both as individuals and as a people, is truly an awesome God!

For a mystical foray into the symbolism of the origins of the universe, the origins of humanity, and how we came to be creatures with free will, I refer you to my Challah Kabbalah post entitled Challah as a Representation of Creation.

Spoiler alert!—we were not gifted with free will; we chose it, took it for ourselves…

So, what shall we eat?

Next week I’ll go back to baking my standard braided challah, but for Beresheet I baked one last round loaf to symbolize the endless cycle of creation.

I defrosted a loaf of salmon gefilte fish, divided it into 8 equal portions, each portion shaped into a “burger,” dredged in flour, and pan fried. Served with shredded daikon radish and horseradish.

Cosmic chicken soup is a riff on ordinary chicken soup. Start with either the classic or vegetarian version. Once the matzo ball batter is ready, separate it into several bowls and color them individually with vegetable powders (think orange, red, green…), leaving one plain. Make the matzo balls in varying sizes to suggest the idea of planets. Add a handful of pasta stars to the finished soup.

A simple entrée of roasted butternut squash stuffed with delicious goodies like wild rice and sausage (turkey, chicken, or vegan), plus apple and cranberries for sweetness and toasted pecans for crunch, took center stage. I added a generous swirl of this gorgeously green savoy cabbage purée and some finely chopped rainbow chard (leaves and stems, quickly sautéed with garlic in olive oil) to finish the dish.

Dessert was a square of rich, chewy, chocolaty coconut brownie with coconut whipped cream. Just perfect! Here’s a secret for fast and easy fabulous brownies:

To1 package Ghirardelli brownie mix, add 2 teaspoons instant espresso powder and 1 teaspoon vanilla bean paste or extract. Replace the oil in the recipe with coconut oil. From there, follow the package directions and sprinkle some shredded coconut over the top before sliding the pan into the oven.